Photo by Chun Kwan

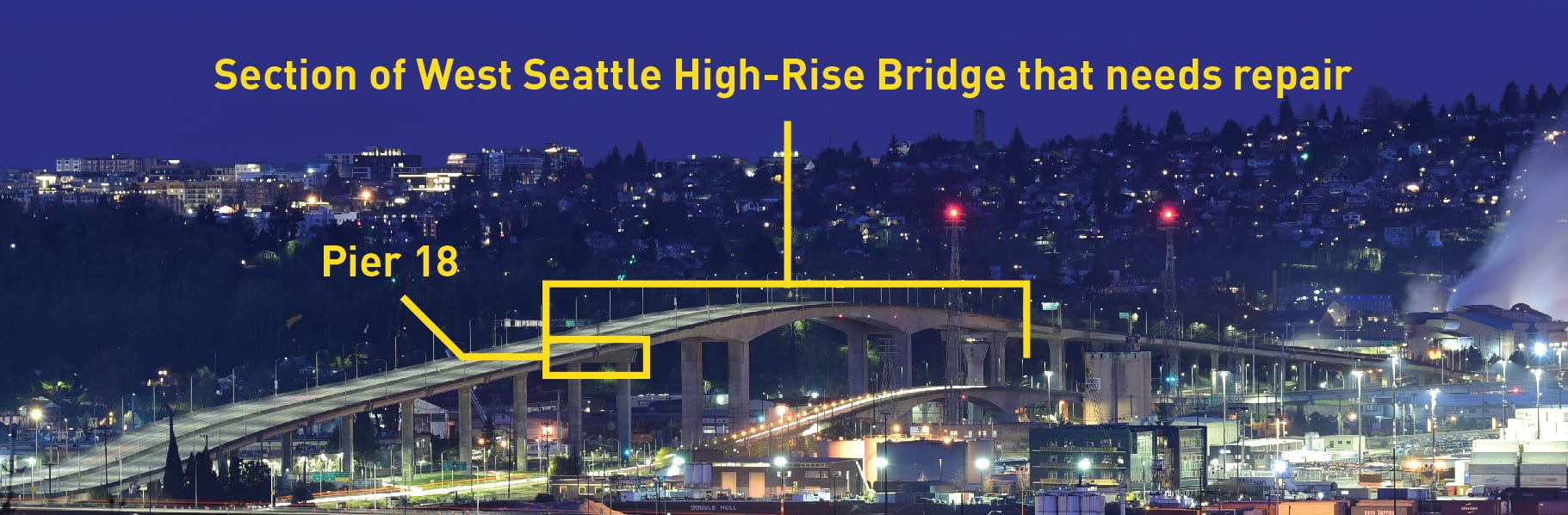

Photo by Chun Kwan To stabilize the West Seattle High-Rise Bridge and potentially help prevent further cracking, we need to replace the lateral bearings on Pier 18.

Last week we shared the news that traffic won’t be returning to the West Seattle High-Rise Bridge in 2020 or 2021 and that we don’t yet know if repairing the bridge is feasible.

We know the bridge closure has profound implications for everyone who works, lives, and travels in West Seattle. As always, your safety remains our number one priority.

During our frequent inspections of the West Seattle Bridge over the past several years, there was no indication that the bridge was unsafe for ordinary use until very recently.

Every day since we closed the bridge on March 23, we’ve been working to gather more information to better understand what’s feasible and fiscally responsible in the long-term. This includes daily in-person inspections and installing a new remote monitoring system that will start sending us real-time data next week and be fully functioning in early May.

We’re simultaneously preparing to carry out the essential work of replacing the lateral bearings on Pier 18 so that we can help ensure public safety by attempting to further slow the cracking. This will also allow us to keep all options for stabilization and repair on the table, for now. After we complete work on Pier 18, we plan to shore the bridge, which involves designing and building an external support structure similar to scaffolding.

Read on to learn more about lateral bearings, what we’ve learned about Pier 18 bearings, why they need to be replaced, and what we hope to learn in the process.

Bridges are designed to take a lot of stress.

Bridges need to stand up to weather events, traffic loads, and natural changes in concrete and steel. Like many materials, concrete and steel expand in warm temperatures and contract in the cold.

One critical way bridges handle that stress is with joints between sections. There are different kinds of joints, but they all work to help make the bridge more flexible and create a buffer between parts that move in different ways.

This mechanism helps isolate stress points and enable a bridge to withstand the various forces that push and pull on the structure.

We discovered that one particular joint has become stuck, which appears to be magnifying the daily stresses on the bridge.

Specifically, the issue is with the lateral bearings at the top of the Pier 18 support columns. This isn’t the sole cause of cracking on the bridge, but our bridge experts think it is a major part of the problem.

The bridge has four main support piers that hold up the three highest spans of the bridge – the part that goes over the Duwamish River, between Harbor Island and West Seattle. Pier 18 is the support structure on the east side of the high-rise span on Harbor Island.

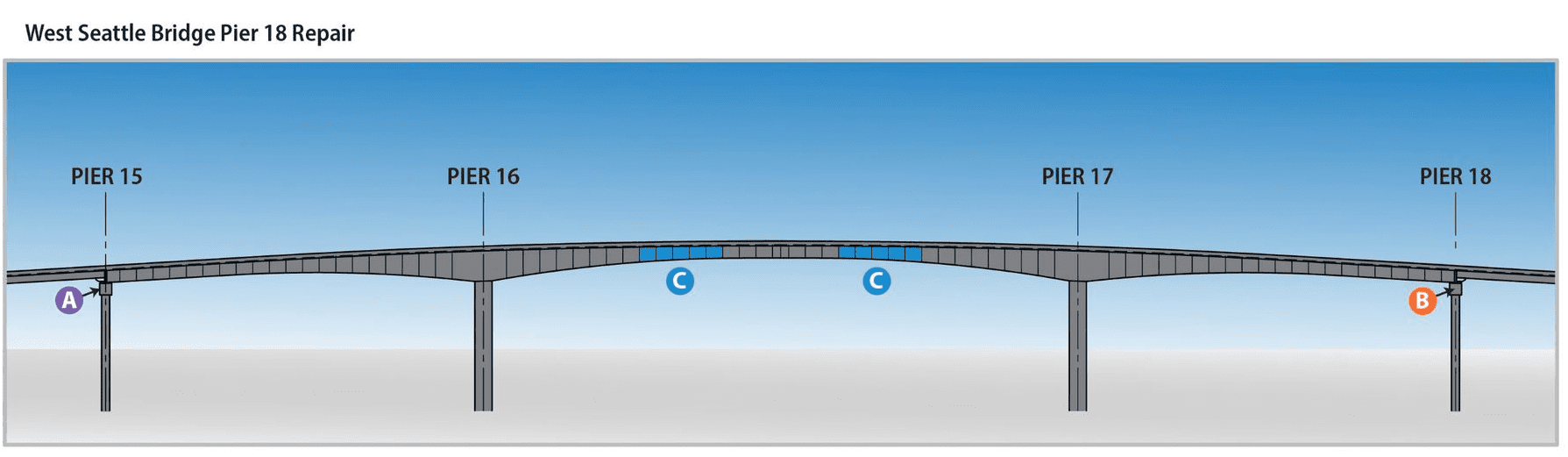

Take a look at the illustration above.

This is a cross-section of the West Seattle High-Rise Bridge showing where a support pier attaches to the bridge structure. To help orient you, that top triangular figure is the median or road divider on the roadway surface. The light gray areas with the six dots are the “box girders”, which are the hollow tube-like structures that form the skeleton of the bridge structure. The thick dark gray area near the bottom is the top part of the support pier, also called the “column cap”. The thin purple lines near the letters A show where the lateral bearings are.

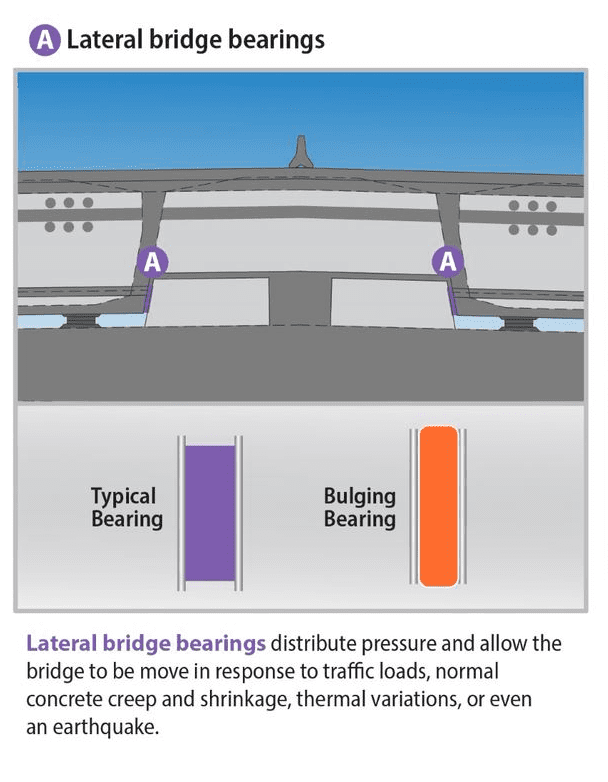

Size-wise, the lateral bearings are a pretty small feature of the bridge, but they play a huge role in allowing the bridge to move in response to traffic, temperature changes, or seismic events.

The lateral bearings are rectangular pieces of neoprene (a synthetic rubber used to make everything from tires to stress balls to industrial equipment) and act like a rubber cushion that separates sections of the bridge.

Like other joints on the bridge, these bearings manage movement. During a typical morning commute, when there is heavy traffic on eastbound lanes of the bridge and light traffic on the westbound lanes, the bearings respond to the uneven distribution of vehicle weight and allow some movement in the bridge.

Even now when there isn’t any traffic on the bridge, the bearings absorb movement from gusty winds and temperature changes that cause concrete to expand and contract.

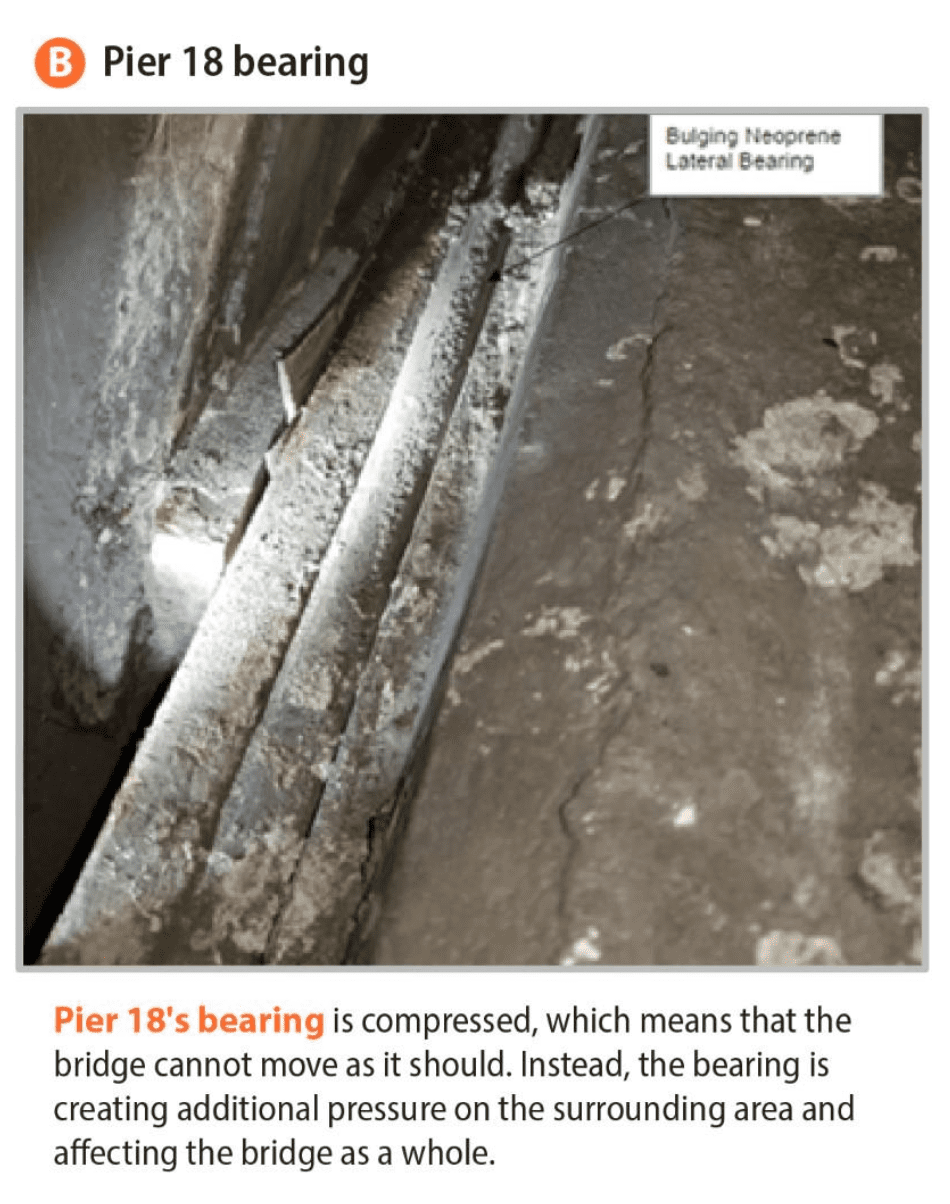

The lateral bearings on Pier 18 are currently compressed and bulging at the top and bottom, locking together two critical parts of the bridge which normally move in very different ways.

When bearings are compressed, they can’t respond to typical changes in weight or temperature as they were designed to do. This limits the motion of the whole structure, causing tension points when there are uneven forces on the bridge. This problem has likely contributed to the accelerated cracking in the center of the bridge.

Our bridge engineers are working to determine the best way to “release” the bearings so they are no longer compressed.

This will likely involve building a temporary platform to perform the work and strengthening some cracked sections of the bridge. Then, specialized equipment will be used to precision-demolish the concrete surrounding the bearings, place the new bearings, and then pour the new concrete.

We’re hoping that releasing the bearings helps stabilize the bridge. If it does, then repairing the bridge may be feasible. If it turns out that releasing the bearings does not slow the cracking of the bridge, it means that the factors contributing to the cracking are much more complicated than just those due to the bearing, and that the bridge structure could be irredeemably compromised.

Fixing Pier 18 is one of the first steps needed to stabilize the bridge.

After Pier 18 work is complete, we plan to “shore” the bridge, which involves designing and building an external support structure similar to scaffolding. This will stabilize the bridge so that the contractors can make repairs.

Some people have asked why this stabilization work is essential.

We still don’t know yet whether it will be possible to ever fully repair the bridge. But no matter what, we do know that it is absolutely essential for us to begin the stabilization process now because it is not safe or responsible for us to do nothing.

Every day we learn more information, and if we no longer believe it’s feasible, technically or financially, we will reevaluate. But, in the meantime, we need to stabilize the bridge to ensure that it doesn’t crack further under its own weight.

As our bridge engineers are working diligently to determine next steps to stabilize and repair the High-Rise bridge, we’re also working to mitigate traffic to help West Seattle businesses and residents and are closely monitoring and maintaining the Spokane Street Low Bridge. We’ll share more about these efforts later this week.

Sign up to receive West Seattle High-Rise Bridge project update emails.

Visit our West Seattle High-Rise Bridge website to sign up for periodic emails to stay up-to-date on the bridge. On the website you will also be able to see frequently asked questions, view inspection reports, and find links to our West Seattle Bridge blogs.