Hing Hay Park reopening celebration in 2018 Photo credit: Seattle Municipal Archives by Sam Fu.

Hing Hay Park reopening celebration in 2018 Photo credit: Seattle Municipal Archives by Sam Fu. The spring month of May is synonymous for Asian Pacific Islander (API) Heritage Month - a time to celebrate the vibrant Asian and Pacific Islander people groups, cultures, and heritage.*

In celebration of National Asian Pacific Islander Heritage Month, we’ll feature in our Roadside Chat series, the rich histories of Asian and Pacific Islanders in the Pacific Northwest and the development significance of Seattle’s Chinatown International District (CID) as one of the very few pan-API neighborhoods in the US.

Asian Pacific Islander, or API, is a racialized identity used by people who identify with Asian and/or Pacific Islander descent. It encompasses the Asian continent and Pacific Islands of Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia.

There’s much diversity among the API languages, cultures, religions, histories, and experiences.

From the first wave of Chinese miners and railroad builders in the 1800s, to the:

- Japanese engaged in fishery and farming in the late 19th century,

- Filipino cannery workers and farmers in the 1920s,

- Koreans seeking professional opportunities in the 1960s and 1970s,

- Washington’s refugee resettlement program that welcomed refugees from Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos in the 1970s,

- Pacific Islanders seeking jobs and education after the US annexation of the island chain that includes American Samoa, Guam, and Micronesia beginning in the 1940s,

- More recent decade wave of South Asian high-tech workers.

There’s a broad range of histories and experiences of APIs in North America.

API’s are a highly diverse group in this country and have made significant contributions and progress to our society, including civil rights activism and community organizing that overturned racially discriminating laws and policies.

The recent rise of anti-Asian violence has long been a part of our history. These include, but not limited to, the:

- Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882,

- Immigration Act of 1924 which nearly entirely excluded Asian immigration to the US,

- Executive Order 9066 authorizing Japanese incarceration in 1942, and

- Practice of redlining and racial restrictive covenants that confined where APIs and other people of color would live and build communities.

These practices that were outlawed in the late 1960s/early 1970s, have shaped many ethnic enclaves across the country, including Seattle’s Chinatown International District. The neighborhood continued to experience injustices imposed on their communities by Federal and local government like the:

- Construction of the I-5 in the 1960s that physically and figuratively cut the neighborhood in half,

- Construction of the Kingdome that encroached the neighborhood in the 1970s, and

- Construction of the Streetcar in 2012.

The most recent Sound Transit 3 Link alignment project is once again bringing CID community members together to advocate for the wellbeing of the neighborhood and hold local authorities accountable for an equitable planning process and outcome. Recognizing the historic harms caused by government, the City has invested financial and staff resources to help build in stakeholder capacity and support the communities role in shaping the future.

The CID has endured many challenges and injustices.

Chinatown International District community members and API’s in the greater Puget Sound region advocated and fought to protect and preserve the neighborhood, and have passed on the torch from generations that came before them, the spirit of resistance and resilience. The Gang of Four, consisted of Bernie Whitebear, Bob Santos, Roberto Maestas, and Larry Gossett, as community leaders and minority rights activists in Seattle in the 1960s-1970s, best exemplified this spirit in solidarity with other communities of color.

To most Seattleites, the Chinatown International District (CID) has long been a destination well known and loved for its small mom and pop shops, dimsum restaurants, bubble tea shops, grocery stores that cater to API palates, and the many fun cultural festivals including the first Night Market in Seattle.

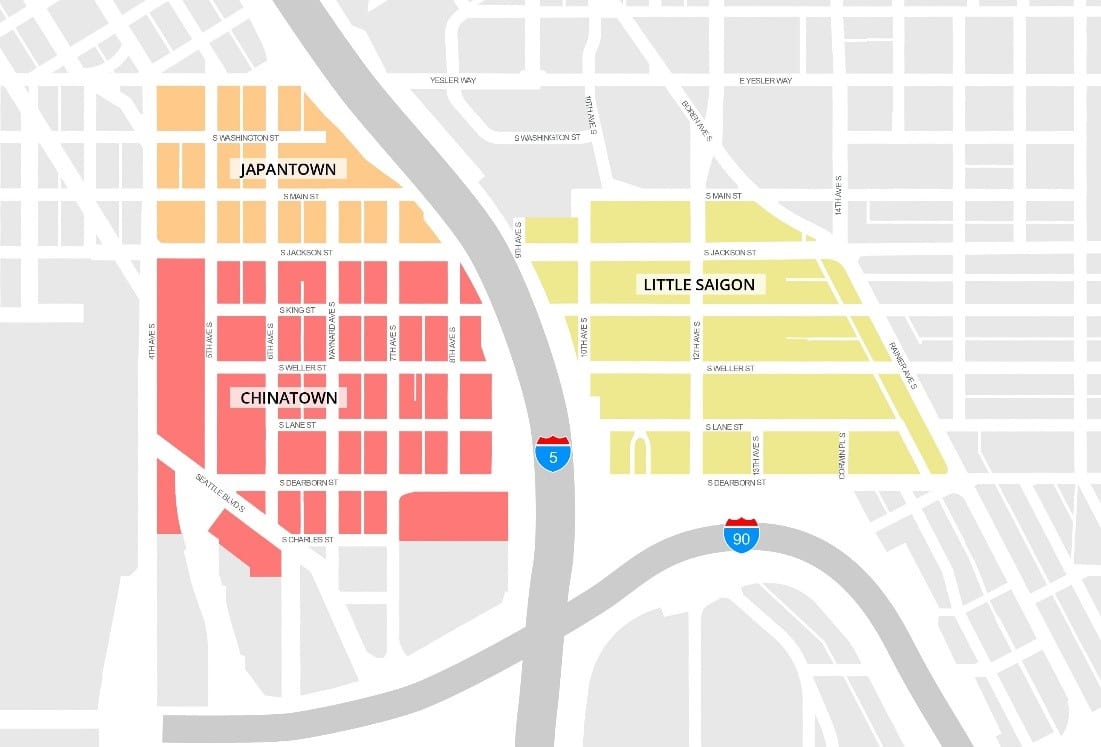

The CID, which consists of Chinatown, Japantown, and Little Saigon, is much more than a weekend destination. Some of the oldest buildings in the neighborhood were built nearly 100 years ago.

The current Chinatown was formed in the early 1900s along S King St. This location is partially due to the Jackson Regrade, which pushed the Chinese community from its former location around 2nd Ave and Washington St.

The many hotels in the neighborhood at that time provided single room occupancy units catered to Chinese, Filipino, and Japanese laborers. Some of these buildings with the very units are still around today, continuing to serve the community by providing affordable housing options for new immigrants and the elderly. It’s worth noting that while the Filipino community didn’t have prominent property ownership in the neighborhood at the time, there have always been a sizeable Filipino residential base in Chinatown and the Filipino community continues to have representation in the CID today.

Like the fate of Chinatown, early Japanese immigrants had geographic limitations to where they could live and build their community.

Japantown, or Nihonmachi in Japanese, was centered on Main St and Jackson St, spanned from 4th Ave to 18th Ave, and bordered the Central District. For many years, the Japanese and Black communities remained good neighbors and thrived together in this area. Unfortunately, due to World War II and the unconstitutional internment of Japanese and Japanese Americans that followed, most of the Japanese community did not return to the Pacific Northwest, leading to a significant shrinkage of Japantown since its heyday in the 1920s.

Finally, Little Saigon was established in the 1970s in the area east of I-5, with the first wave of immigrants from Vietnam and other parts of Southeast Asia.

The built environment in Little Saigon is noticeably different compared to the dense and urban fabric of Chinatown and Japantown just west of the freeway. The area where Little Saigon is located was previously zoned for industrial use and thus mainly consists of large warehouses and industrial buildings. These buildings became the perfect spaces for the many well-known grocery stores and restaurants that serve as anchors to Little Saigon.

To this day, the CID remains a vibrant neighborhood with bustling small businesses, diverse residential demographics, well-used parks, a community center, social service agencies, medical clinics, cultural institutions, and home to the Danny Woo Garden – a community garden with some of the oldest gardeners (with the average age 76!) in the city.

The CID is also a major regional transportation hub, with access to over 30 bus routes, Link Light Rail, First Hill Streetcar, Sounder Train, Amtrak, and a growing connection to the Center City Bike Network.

Did you know that the CID is one of eight Historic Districts in Seattle?

This snapshot of the CID history is meant to help us understand and appreciate how the API communities have overcome some of the harshest systems of racism and created its own vibrant microcosms.

While we celebrate the vast and beautiful API cultures and their astounding contributions to our transportation network, we also acknowledge racism in our city and country and recent violence against Asian Pacific Islander communities and people. We can do better. In our next Roadside Chat blog series, we’ll share stories of community stewards who are creating space for their communities – so stay tuned!

We encourage you to learn more about the Asian and Pacific Islander people’s experience in Seattle.

- Our friends at the Seattle Department of Neighborhoods are hosting a series of profiles and stories to amplify and honor people, businesses, organizations, and projects connected to the history of Seattle’s API community.

- Visit the Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific American Experience, named after the first Asian American to hold public office in Washington State.

- Browse this timeline of Asian American history in Washington State, provided by the University of Washington.

- Visit the Seattle Asian Art Museum at Volunteer Park

We also encourage you to support local API-owned businesses and restaurants, both in the CID and throughout Seattle and the region.

- Search Intentionalist for Asian-owned restaurants in Seattle

- Looking for a specific type of food? Seattle Eater has articles highlighting a variety of Asian and Pacific Islander cuisines and restaurants.

- Visit SeattleChinatownID.com or Visit Seattle for shops, restaurants, and places to visit in the CID

Dragon Fest 2017 in the heart of Seattle’s historic Chinatown-International District. Photo credit: SDOT Flickr

Hing Hay Park. Photo credit: SDOT Flickr

Do you identify as API? Share your story with Our Stories are Your Stories (OSAYS), a grassroots awareness campaign highlighting API voices through video storytelling. Recorded stories will be archived at the Wing Luke Museum.

*We recognize there are different terms used to describe the Asian Pacific Islander racial group and these may continue to evolve and change over time. For this blog post, we chose to go with Asian Pacific Islander to include immigrants and refugees of Asian Pacific Islander descent regardless of their citizenship status.